The history of women in the Olympics

I don’t give a damn what people say about me. I like me the way I am, and who cares what other people say?

— Caster Semenya

HISTORY OF WOMEN IN THE OLYMPICS

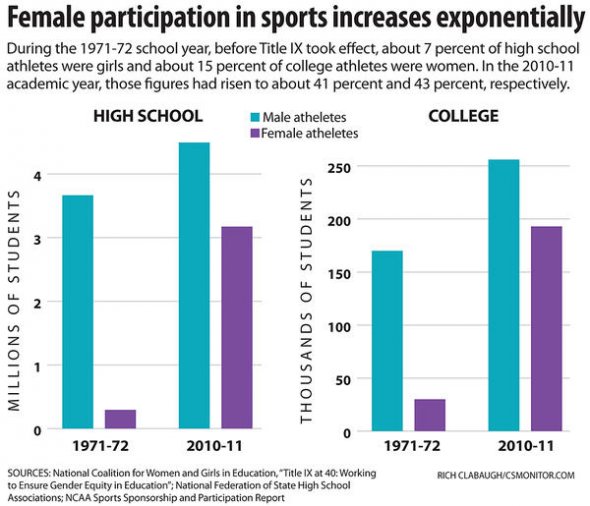

The first MODERN Olympics (Held under the International Olympic Committee/IOC) were held in 1896. In 1900, women were allowed to participate in the games in Paris. Only twenty-two of the athletes were women, making up 2% of the nearly one thousand participants, competed in tennis, sailing, croquet, equestrian, and golf (However, women weren’t allowed in equestrian until 1952).

By 1928, female participation reached nearly 10% and could now take part in sports such as archery (1904), Skating (1908), Aquatics (1912), and gymnastics (1928).

Female participation in the 1960 winter games (Squaw Valley, California) reached 20%.

Many sports began allowing female participation: Skiing (1936), Canoe-Kayak (1948), Volleyball and Luge (1964), Basketball (1976), and (Field) Hockey (1980).

In 1981, Flor Isava Fonseca and Pirjo Häggamn were the first women co-opted IOC members. By 1990, Isava Fonseca became the first woman elected on the IOC executive board.

In 1991, the IOC declared that any sport that wanted to become an official Olympic sport needed to also include women’s events. In 1995, they implemented the “Women and Sport Working Group” whose goal is to work with the executive board to implement policies for gender equality.

The first “World Conference on Women and Sport” took place in 1996. In 1997, Anita DeFrantz became the first women Vice-president of the IOC. The 2000 “World Conference on Women and Sport” declared that by 2005, at least 20% of decision-making positions must be held by women. In 2000, they also introduced the IOC Women and Sport Awards to promote the advancement of women in sport. In 2013, four women became members of the IOC executive board (26.6%). In 2014, Women made up 40% of participation in the winter games (Sochi,Russia). Also in 2014, 49% of the participants in the Youth Olympics were female.

Two years later, in the 2016 summer games (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), Females athletes made up 45% of the participants.

In 2018, the youth Olympic games (Buenos Aires, Argentina) had the very first fully gender balanced Olympic event ever, where both males and females are both on the field. Female representation on IOC Commissions rose to 42.7 %, which was a 98% increase from 2013. As of 2019 , 33% of IOC members were female. In the 2020 Tokyo games, Women will be able to compete in softball, karate, sport climbing, surfing, and skateboarding. as well as Nordic combined (Ski cross county + Ski Jump) in the 2022 Winter games in Beijing, China.

(Source: https://www.olympic.org/women-in-sport/background/key-dates)

Sex testing in the Olympics

Sex testing is a very infamous part of the Olympics. During the Cold War (1960s), there was irrational fear that the Soviets or the Americans were disguising men as women in order to win more medals. So the new rule was that all women competing in international events needed to undergo their idea of a sex test. Their idea for sex testing at the time was a “nude parade”, where female participants would be forced to walk before a panel of judges in only their undergarments and then show their genitalia in order to prove that they were female. As you might have guessed, there were many complaints (rightfully so) about this “test”, so the IOC and the IAAF (International Association of Athletics Federations) decided to drop it, in favor of a chromosome test (Barr body). which tested for X’s and Y’s by examining cells on the inside of the cheek. While this test might seem better, as it looks at genetics and isn’t invasive/degrading, this test still has a major flaw. The IOC claimed that the test “Indicates quite definitively the sex of a person”. When tested, Ewa Klobukowska of Poland, failed the test, due to having both XX and XXY chromosomes. Geneticists and endocrinologists rejected this test by saying gender isn’t based on chromosomes, rather genetic, hormonal and physiological factors all had a role, arguing that the tests also targeted anyone with abnormalities.

By 2000, they scrapped chromosome testing, and the some sports got rid of gender testing entirely. But, in 2009, 18 year old Caster Semenya of South Africa, beats the world record by 2 seconds. The rumors start spreading about her “true” gender. It got so out off hand, the IAAF had to investigate her. The IAAF banned her from racing, and ended up reinstating gender testing, needing to have this clear line, between male and female athletes.

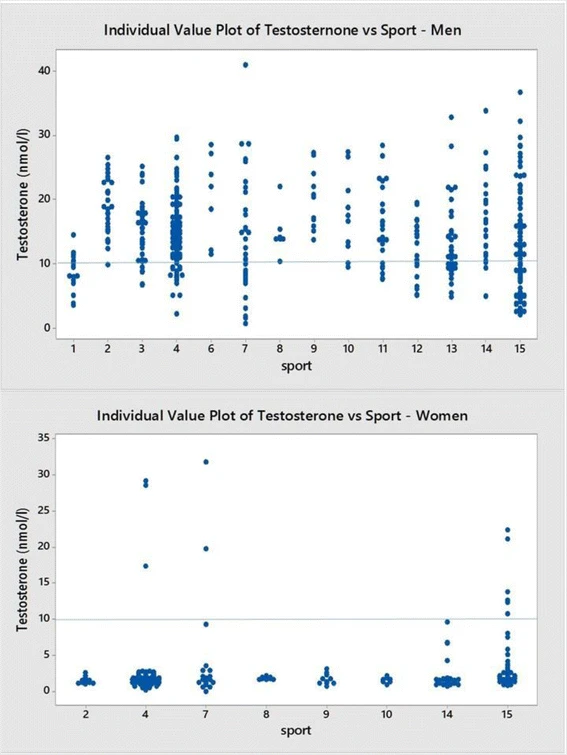

The IAAF decided that they would now look for hormone levels, more specifically, Testosterone levels. In 2011, they tested for high testosterone levels, and if a female fell within the “male” range, they couldn’t compete. After many studies, the IAAF finds out that testosterone only has a small impact on performance, and only impacts “middle-distance” races. As of May 1st, 2019, the IAAF cap for women is 10 nanomoles per litere (Most females have natural testosterone levels of between 0.12 and 1.79 nmol/L in their blood).

The IAAF found that “7.1 in every 1000 elite female athletes have elevated testosterone levels – the majority in events from 400m to the mile.”

(Sources: https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/radiolab/articles/dutee https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/03/magazine/the-humiliating-practice-of-sex-testing-female-athletes.html)

Sport numbering: (1) power lifting, (2) basketball, (3) football/soccer, (4) swimming, (5) marathon, (6) canoeing, (7) rowing, (8) cross country skiing, (9) alpine skiing, (10) weight lifting, (11) judo, (12) bandy, (13) ice hockey, (14) handball, (15) track and field.

Source: Sönksen, P. H., Holt, R. I., Böhning, W., Guha, N., Cowan, D. A., Bartlett, C., & Böhning, D. (2018). Why do endocrine profiles in elite athletes differ between sports?. Clinical diabetes and endocrinology, 4(1), 3.

Media links: “How Caster Semenya’s case could alter the landscape of women’s sport”

Fun fact: The first woman to be listed as an Olympic victor was Cynisca of Sparta in 396 B.C.E

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/64683515/1160608491.jpg.0.jpg)