History of women in baseball

The best place to start talking about women’s baseball is too talk about Lizzie Murphy.

In the 1920s, Lizzie played Providence (Rhode Island) Independents as a first baseman and was widely regarded for her fielding ability. She was paid $300 a week (which would be about $3,5858 in 2019), more than most minor league players at the time. Her career lasted from 1918 to 1935. Her dream was to make it to the major leagues, but couldn’t make it, but made it to the semi-professional league.

Then World War II came. During WWII, over 500 major league players were drafted, including icons such as Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and Joe DiMaggio (Source). In order to keep the major leagues financially stable during the war, a committee formed the “All-American Girls Professional Baseball League” (AAGPBL) from 1943-1954.

Ila Borders was the first ever female to start a men’s professional baseball game. Ila played from 1997 to 2000, having 52 appearances, 2-4 record, and 36 strikeouts.

In 2008, Eri Yoshida became the Japan’s first ever female baseball player drafted in a professional men’s league, at age 16. In 2010, she signed a contract with the Chico Outlaws (in California), becoming the first ever woman to play professionally in two countries.

In 2009, Justine Siegal became the first female coach of a professional team, becoming the first base coach for the Brockton Rox (part of the “Can-Am League). In 2011, Siegal became the first woman to have throw a MLB batting practice, for the Cleveland Indians. In 2015, the Oakland Athletics hired her for two weeks as a guest instructor for their instructional league, thus making her the first female coach for a MLB team.

The differences in elite female and male pitchers

The purpose a 2009 study from University of Georgia and the American Sports Medicine Institute was to “Identify the biomechanical features of elite female baseball pitching”. The study examined the kinematics (motions) of eleven elite female and male pitchers, using a high speed camera.

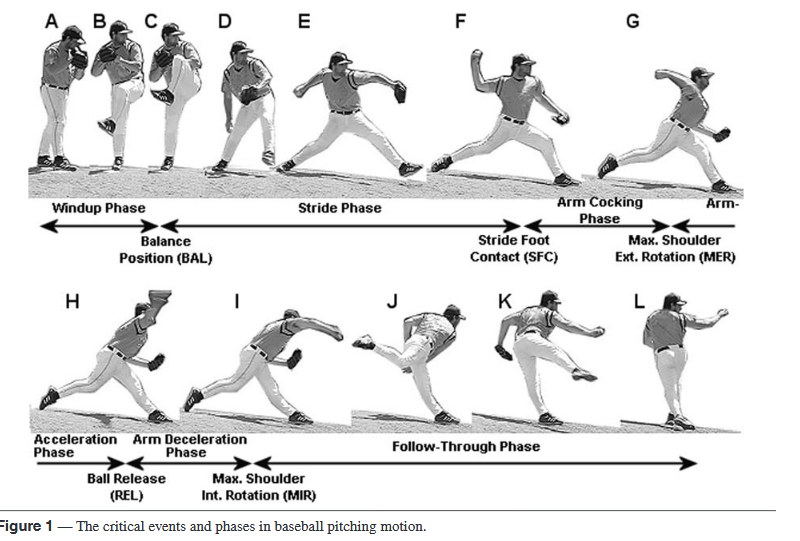

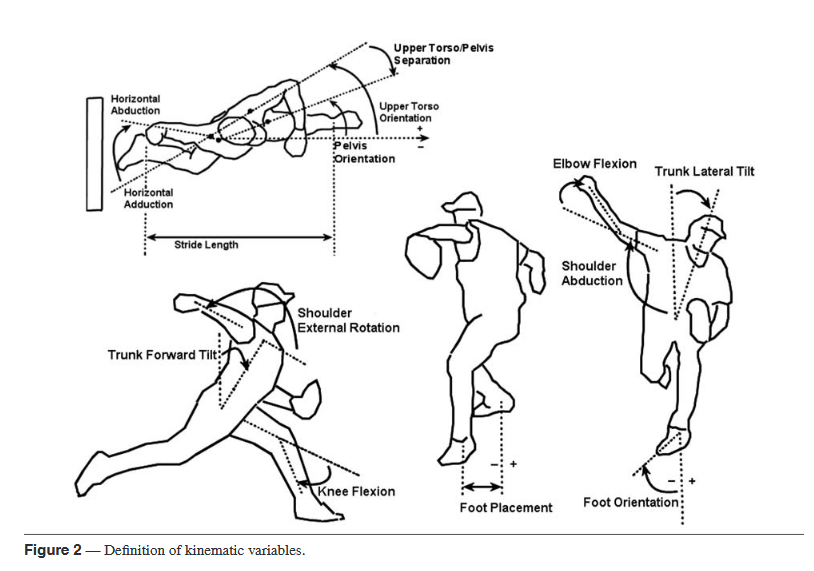

The results of the study showed that females had significantly slower ball velocity. It was also found that females had smaller a smaller stride length and a more open foot stride (front leg was farther out to side during stride), and less upper torso/pelvis separation (distance between the “pelvis orientation” and “upper torso orientation” (fig.2). The study also found that females had less elbow extension velocity (how fast it extended) and less stride knee extension velocity. The study also found that females had a higher knee flexion when releasing the ball (knee was bent more by the time the ball was thrown). It was also found that, for the females, “stride foot contact to ball release” was greater, meaning that it took female pitchers longer to release the ball after the “stride” foot went back down (see fig. 1: B-F phases).

In the discussion section, the study talks about how velocity differences could be explained by the fact the female pitchers tended to rotate their pelvis and upper torso less than the male pitchers. One of the biggest differences that females only lifted their stride leg 3.2 cm above the hips, while males lifted their stride leg 33.1 cm above the hips. The researchers attribute this to the possibility that “due to less muscle strength for females to rotate the trunk back and keep the balance with a high leg kick”. The study also talks about due to the shorter stride and lower leg kick (CDE fig 1), there could be less usable potential energy in the throw. Females also generated 31% less elbow velocity. Ball velocity was found to be significantly lower, and the researchers attribute it to less elbow extension velocity and less knee extension velocity.

The study talks about one of the limitations of the study, and it is a pretty glaring issue.

“although participants were selected to represent elite amateur pitchers in both genders, the female pitchers are real “amateurs,” whereas the male Olympic pitchers may have experienced some professional training in both facilities and schedules.”

The study concludes by saying how though there many differences were quantitative, overall, pitching mechanics were not very different between males and females. The study goes on to suggest that these can be fixed. Open foot placement can be worked on with a pitching coach, while upper torso/ pelvis separation and front knee extension would need technique instruction and strength training.

(Source: Chu, Y., Fleisig, G. S., Simpson, K. J., & Andrews, J. R. (2009). Biomechanical comparison between elite female and male baseball pitchers. Journal of applied biomechanics, 25(1), 22-31.)

Media Links:

Eri Yoshida – AP